Charles Smith

Interview with Charles Smith

by Brittany Myburgh

September 17, 2022

Charles Smith is one of the Department of Art at Jackson State University’s most notable alumni. Based in Mobile, Alabama, Smith attended Jackson State in the 1970s and has exhibited at the National Museum of American Art in the Smithsonian Institution, as well as in the American Craft Museum in New York City. Smith studied ceramics under Marcus Douyon, an esteemed Haitian intellectual and the Department of Art’s first ceramics instructor. As part of a research project into Marcus Douyon’s life and practice, I was fortunate to speak with Charles Smith about his time at JSU and his subsequent career as a nationally renowned ceramicist. Excerpts of this interview are published here as a special alumni feature.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me, Mr. Smith. First of all, I have to ask about your time at Jackson State. I would love to hear how you reached the decision to attend?

Well, I went back to school when I got out of the military. I’m a Vietnam veteran. I went back to junior college in Mobile and I went in as a business major, just to take general studies. I took ceramics as a course requirement, because we had to have some kind of art education. I studied with Edmond Dean, who was the instructor at that time. I was drawn to clay because it stopped my mind from wandering, and because we didn’t have art classes in public school, so that was sort of new to me. And I just kept with it, and did a body of work at Bishop State. When I wanted to move on to somewhere else, I found out that Jackson State had a ceramics program. So, I called over to Jackson State and I talked to Lawrence Jones, and I told Mr. Jones that I was at Bishop State. I said I wanted to transfer over to Jackson State and that I was a ceramics major, and that I needed some financial assistance. Mr. Jones told me that he didn’t have any scholarships. So I just asked him, “Can we make an appointment so that I just come over to Jackson and have you look at my work?” He said, “well, you come over.” Edmond Dean went with me once I told him what was going on. When we got to the ceramic studio, Marcus Douyon, the ceramics professor, was there and looked at the work. And then when Mr. Jones came in, Lawrence Jones looked at it and then they went to the side of the room and they talked.

Were you nervous?

No, I didn’t feel nervous, you know, not really. I was just going through the motions. It was a one shot deal because he already said he didn’t have any scholarships. They looked at the work and then Jones told me to wait there. He was gone for about half an hour. When he came back, he told me I had a scholarship.

They saw the potential. I look at the work now, and they were looking at a sort of work in progress. They saw my work and thought, he’s got something going on here, he’s disciplined, he knows what he wants. So I got the scholarship and I studied under Douyon for three or four years. We became friends until he passed. Douyon would pick the best students that he knew, about five or six of us that started out together, and these were the ones he knew were really into ceramics versus just coming there to get a grade and move on. And then when that group of five or six would get a body of work done, maybe it wasn’t craftsmanship, but it was marketable. It was marketable and he would tell us this would be an assignment. So he would send us out to the Canton flea market. He said you need to sell it, then you can know what the public thinks about it. Then he would send us to some of these elementary schools and middle schools to do demos, and that was part of the program.

So he really encouraged that connection to the community?

Well, and getting out into the real world. Because being a Black artist, having a venue to sell your wares was hard to come by. It was hard to try and spend my time selling something in mainstream America being Black. And the way Black people got into the craft side of it was through the Mississippi Craftsman Guild when they started in ’74. I was still in school and I applied the first year and I got rejected. And at that developmental stage the thing is that it’s good to get rejected. Because I would just go and refine my work, and then the next year I got in. And, and then they started seeing Black artists doing ceramics. Because you still have people saying this thing, that they’ve never seen a Black person doing ceramics. Well, we’re all over the place.

At JSU we still have a strong ceramics program but we’re also talking to students about the long history of Black ceramicists, like David Drake, and about Afro-Carolinian face jugs. Do you see your work as part of that history now, do you think about that legacy?

The thing about that is, being part of history is not for everybody. You think about David Drake, what was he doing? He was talking in code. Maybe not talking to the contemporary viewer, but he was talking to the next generation. Cause the next generation had to figure his story out. He was documenting the place and time. That’s what ceramics is. So how I see it, is somebody has to be out there knowing that they have to make art. Because other people, they’re tied up in their own music. They have to go to work. They have to take care of family. They have to go through the standard regime. But who is going to be the one to step to the side and document that? That’s what the artist’s job is, to document the moment, to let people know that I existed, that we existed, because if it wasn’t for that stone with that writing inscribed, well you wouldn’t know it.

So at some point, well I felt I have to do it. This is my calling. It’s as simple as that. I can get an income, and maybe not get rich, but I’m here for a purpose. I can’t get rid of it because now it’s a passion. I tried to get rid of it for a long time, because I just felt like I couldn’t find my style. I went to the library, and every day I would look at the books, but it was always somebody else’s stuff. I would look at precolonial art, Native American, African art. I couldn’t find it. And I was just beating myself over the head for years because I had stuff that was sellable, but it didn’t have my signature on it. But I was looking for something that was already right there. And it just dawned on me one day it’s like making a cake.

You had all the ingredients?

I had all the ingredients. I just had to put them together. You know, I went through my phase of writing stuff on the bottom, and this is going back to Drake as well. Charles Smith is such a common name; I knew I had to do something that would counteract that because there’s about six Smiths in every town, so the pots should stand on their own. The first thing you should know is that pot is one of mine. And you learn the process. Don’t fall in love with it until you’ve fired it. You have to know the process, and the way you set up your working environment, you have to continue doing that step by step by step – don’t break it. And that’s what it’s like going into that ritual. That’s respect for the material. This is a living breath or something like it, so I have to pay homage to it.

Did Douyon also talk about process and ritual? Did that start at Jackson State or was that something that for you came later?

Oh, that came later. That’s when you get to the point of being a professional and you don’t waste what you have. Once you get to that professional status, you can’t have any bust ups because that’s income. And there’s a lot of soul involved in it. If I have a pot and it blows up, I don’t throw it away. I don’t put it in the trash. I’ll put it in a paper bag on the shelf somewhere, or take it outside and bury it. There’s too much heart in it. There was time involved in that, you know, the thinking of it, the laboring over it, the energy going into these different little things that you create for yourself. And then to pick up the pieces, take the bag, throw it in the trash can? No. We go through that grieving process, and we’ll bury it or put in a brown paper bag because this way we can recycle it somewhere down the line.

That’s something that you become mindful of when you start working with natural materials. That really is not written. It’s just something artists pick up, that you have to pay close attention to nature, and you think maybe these things could be resituated or I could ground it down and then put it into something else. Some of the things that I do are all about studio and studio timing, knowing when to make your move, because you are putting out a precious product. And you need to have your own space, so you can understand that space because that space is going to breathe, it’s going speak to you. That’s your sanctuary. You need to have your own music. You need to have your own timing, because in some cases you just have to go into that zone and just be all about you.

That ritual, that evolvement, takes years before you even know that you are doing it. And the work is evolving with me because of age. So when I was young, I could do a straight line. I could do a fine line and wouldn’t even waver from it. It would be straight as an arrow, but as I’ve gotten older, I can’t see as well as I used to, I can’t shift my feet like I used to. So the pot might be a little lighter than it used to. But the design is bigger because I can’t see as well, so I have to have the design a little bit bigger compared to what it was 30 years ago. That’s what evolvement is and I can tell the difference with the line, you know, all that kind of stuff.

So, you mentioned what it meant to be Black studying ceramics at that time, and changes in access to exhibitions and markets and things. When you were graduating from Jackson State, did you ever imagine that you would end up in places like the Smithsonian?

No. I graduated from Jackson State with a degree in education. The thing that got to me was that I didn’t know I had PTSD from the war. This was before the fact of knowing about that, and I didn’t care that much to be around people and I stuck with ceramics. When you get into that zone and can do your own little thing, then you can have your quiet time.

When I got out, the art scene had just started kicking in. We did a few shows around Jackson, but they weren’t big time shows, just some little shows in the park. But what happened is that with the hippie movement, you know during the Haight-Ashbury era, you started having people coming in and starting these communities, and start having these little weekend shows just to get out to the public, to make a little money. So we would also go out there and set up shows, and they weren’t well organized. We’d pack up and go to this or that little show for the weekend to make some money. And then somebody would give you another date. Another. You’d apply to it and they’d just send you an invitation. You’d go do that. And then the next thing, over a period of years, you have a little cycle board. The more you do it, the artists start getting better at their displays, start looking at each other’s displays. Then these markets started getting more developed. You started having promoters come in. That worked well for about 20 years, but promoters got greedy.

It wasn’t the game plan. That just all happened. I just stuck with the way I worked, just one pot, one at time. I always stayed with ceramics. I was doing that in the back of my mother’s garage, and my parents didn’t understand. They said wait a minute… he graduated college, he’s a grown man, but he’s back playing with that clay? But there was a market out there and it was a viable area where you could go out there and make a living. Once I left home and got my own place, they finally started seeing it. I’m glad before they passed away that they saw that I could do this.

Did you ever have a defining moment where you felt like this is it, I’ve made it, I feel successful at what I do?

I was in this thing for about 20 years before I figured that out. It didn’t dawn on me until after everything kicked in where I had that muscle memory and I knew what I wanted to create. I was in total control of what was going on. And after going through all that process of breaking stuff up and throwing stuff, it kicked in one day that this is my calling right here. And it was through just working and working and working. You know, I was raising kids with my wife Catherine as well as making work and all of a sudden one day I felt it. I’m free. It was a life altering event. It was a big old wake up that this is what freedom is to me. I could make what I wanted to and still get paid. I have an audience and I don’t have to worry about museums. I have people that believe in me and these people pay money that supports me.

That’s the thing, you know, those people would come in when you had those lean years, or those lean times, that were good collectors. They cared about the artists and they knew how to operate because they were in the art scene. And these people and artists were part of their investment as well. That’s it, it’s to have those people who believe in you.

It reminds me of the beginning of our conversation when you said Lawrence Jones and Marcus Douyon believed in your potential, and how important that investment in artistic potential is…

Right. And the thing is that, when I got in, I pulled two or three other people behind me up and they got the same treatment. All Edmond Dean had to do was call Mr. Douyon or Mr. Jones and give the student’s name. Because they knew where they were coming from. They knew what that discipline was.

That’s an amazing network to form.

Oh, they charged each other’s batteries. And you need that, to be around other people with the same thinking. And Mr. Jones and Mr. Douyon would always visit shows and give me encouragement. Same thing with Willie Cook. I mean, students had a love hate relationship with him. He was a good guy, but a task master. He would grill you with color theory. He was a smart guy. It took me years to figure out, because I was young and didn’t know it, but he planted a seed for my work. When I got to the point of wanting to find my own style, Mr. Cook said to me, I know you love ceramics and if you took some of these drawings that you are doing, and you put them on your ceramics, you have an ace in the hole. 20 years after the fact, when I was looking for something for my style, that’s when I started having that aha moment. I went back and looked at some of those drawings. Yeah, he was right.

Thank you so much, Mr. Smith, for taking the time and I’d love to stay in touch as well if we can.

Oh yeah, I’ll send some photos. And I have a granddaughter at Jackson State right now, she’s in the band, all my children all graduated Jackson State.

Go JSU! I really appreciate it, Mr. Smith, thank you for contributing to the history of Jackson State.

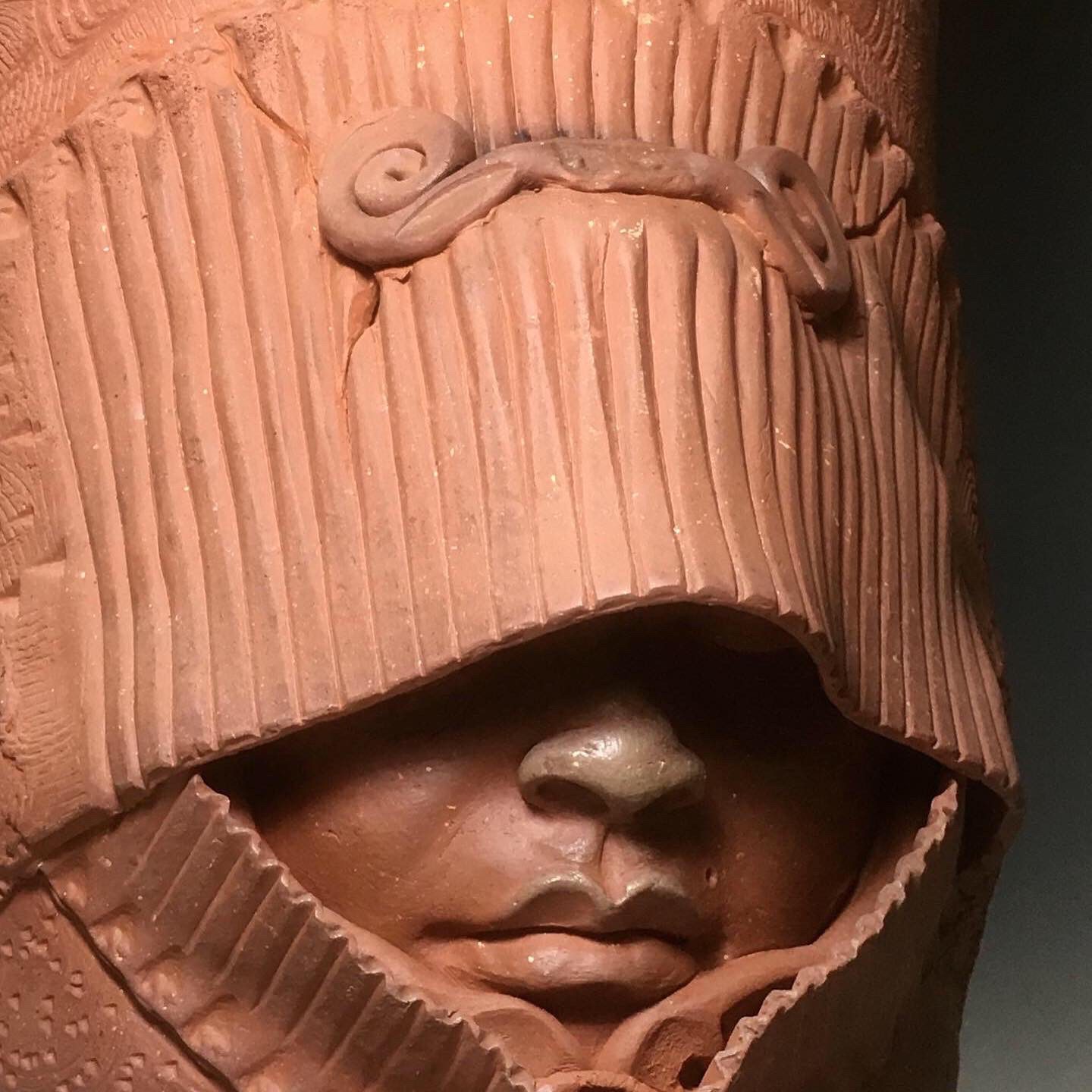

More information about Smith’s practice can be found in the catalog for “Black Hands/I AM,” an important retrospective at the Mobile Museum of Art.

To contact Charles Smith regarding his work you can direct all enquiries via email.